Lud-in-the-Mist: "one of the least known and most influential of modern fantasies"

Part one: overview

Lud-in-the-Mist. Hope Mirrlees.

Orion Publishing Co, 2018. Also available on Kindle. First published 1926.

Hope Mirrlees’ novel Lud-in-the-Mist is a link between nineteenth century fantasy writers, such as Lord Dunsany and George Macdonald, and modern authors; it precedes Tolkien’s Hobbit by 11 years, and the Mary Poppins series by seven. One reviewer remarks that it is “by turns and sometimes all at once, an eerie fairy tale, a ghost story, a murder mystery, and an adventure.”

Neil Gaiman has heavily promoted it, and it’s been said that his own story Stardust “draws verily heavily” on Mirrlees’ tale. Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell has clear parallels. And yet it has been almost entirely lost to modern readers. As her biographer writes, “Lud-in-the-Mist is simultaneously one of the least known and most influential of modern fantasies”.

Because it is so little known, and because there’s so much to say, I will discuss it at length, across three posts: an overview of the story; a look at the presentation of Faery in the novel; and a consideration of it as a novel of ideas.

The setting

Lud-in-the-Mist was the capital of the small Free State of Dorimare. It was staid and stolid. One of the first images is of flowers hidden away, “imprisoned in a walled kitchen-garden”.

The city lay at the confluence of two rivers. The broad Dawl brought commerce and prosperity, but the narrow Dapple flowed out of Fairyland, or Faery, which lay to the west, beyond the Elfin Marches and the Debatable Hills. From Fairyland came illicit fairy fruit: those eating it were prone to “madness, suicide, orgiastic dances, and wild doings under the moon. But the more they ate the more they wanted, and though they admitted that the fruit produced an agony of mind, they maintained that for one who had experienced this agony life would cease to be life without it.”

Two hundred years prior, the land had been ruled by a debauched, decaying aristocracy with open borders to Fairyland and living by that land’s nature-focused old religion. The last of these lords, Duke Aubrey, was known for wanton destruction, and “dealt with the virtue of his subjects’ wives and daughters in the same high-handed way.” During country marriages, when the bride “was ritually offering her virginity to the spirit of the farm, symbolised by the most ancient tree on the freehold, Duke Aubrey would leap out from behind it, and, pretending to be the spirit, take her at her word.” He drove his own court jester to suicide through subtle measures to make the fellow ever more sad – a triumph that gave the Duke lasting delight. Yet at other times he was compassionate and effusively generous to those in need.

He was toppled by a rising merchant class, and vanished, “some said to Fairyland, where he was living to this day”. The new bourgeois rulers promptly debarred all fairy things. They also detached from common folk, who remembered the old ways fondly. But the fairy-rich past lived on. In the olden days, there’d been frequent intermarriage between them and the fairies. The past also lived on in sayings, names, turns of phrase. And houses showed

traces of an old and solemn art, the designs of which served as poncifs to the modern artists. For instance, a well-known advertisement of a certain cheese, which depicted a comic, fat little man menacing with knife and fork an enormous cheese hanging in the sky like the moon, was really a sort of unconscious comic reprisal made against the action depicted in a very ancient Dorimarite design, wherein the moon itself pursued a frieze of tragic fugitives.

The story

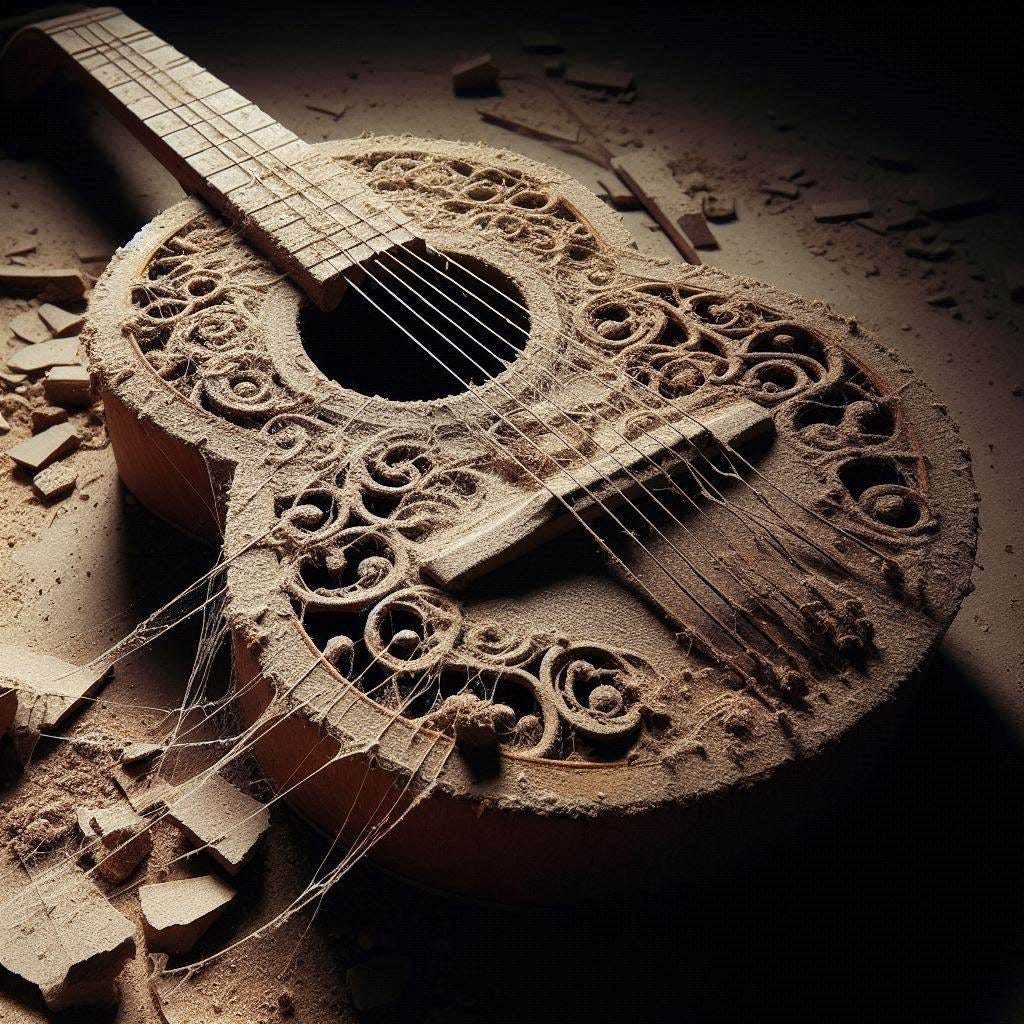

In his boyhood Nathaniel Chanticleer chances upon an old lute from former times, on which he strikes a single note, “plangent, blood-freezing and alluring”. The Note becomes “the apex of his nightly dreams”, while by day he grows anxiously, compulsively attached to everyday humdrum things.

He was born into the ruling merchant class, and in time becomes the city’s worthy Mayor. Among other things it is his duty to stamp out the smuggling of fairy fruit into the land of Dorimare. But his own son Ranulph starts behaving oddly, after receiving such fruit from the itinerant stable-hand Willy Wisp.

Chanticleer goes to the skilled if disreputable doctor Endymion Leer, who persuades him to let Ranulph stay at a farm near the Elfin Marches. There the boy’s behaviour grows even stranger, until he takes off toward Fairyland. Meanwhile a certain Professor Wisp leads Chanticleer’s daughter Prunella, and other well-bred girls, in a strange wild dance; soon they too run madly away to Faery. Chanticleer, trying to stamp out the smuggling and also rescue his children, is drawn into a murder-mystery which dominates the middle of the novel.

(Spoiler alert:) Chanticleer and one of his peers solve the murder mystery (with deft but low-key help from his wife). He then concludes he must do the unthinkable and enter Fairyland to rescue his son, daughter and the other girls. On the borderlands Duke Aubrey appears, and gives him vivid but ephemeral visions, in which the dead perform everyday scenes from life, in a lifeless way; some visions show his son and the girls in misery. He pushes on, and in the end literally takes the plunge, into an abyss of blackness, after which the scene returns to Lud. The girls return from Fairyland one by one, each with a different hallucinatory-sounding tale, but all saying they were saved by Chanticleer. He himself then returns as the Duke’s deputy with an army from Fairyland – an army of the dead, with priests from the old religion.

The merchant class stays in power, but now with open borders to all things fairy. Endymion Leer and a mortal ally are revealed as servants of the Duke, who has however made mocking use of them; even when they pursued their own interests the Duke had contrived things so that they served him, while undermining themselves.

The next part of this series will examine the novel’s portrayal of Faery.